For Thomas Aquinas, the mistreatment of another person’s animal would be sinful, not for the sake of the animal in itself, but because it is someone else’s property. For Augustine, animals were part of a natural world created to serve humans (as much as the “earth, water and sky”) and humankind did not have any obligations to them. This view of humans as superior would later influence and underline the Judeo-Christian perspective of human dominion over all nature, as represented by texts by Augustine of Hippo (IV century) and Thomas Aquinas (XIII Century), the most influential Christian theologians of the Middle Ages. The supposed likeliness of humans to their anthropomorphic deities granted them a higher ranking in the scala naturae (“the chain of being”), a strict hierarchy where all living and non-living natural things-from minerals to the gods-were ranked according to their proximity to the divine.

įor most ancient Greeks, using live animals in experiments did not raise any relevant moral questions. These remained canonical, authoritative, and undisputed until the Renaissance. All of these authors had a great influence on Galen of Pergamon (2nd–3rd century CE), the prolific Roman physician of Greek ethnicity who developed, to an unprecedented level, the techniques for dissection and vivisection of animals and on which he based his many treatises of medicine. The latter two were Hellenic Alexandrians who disregarded the established taboos and went on to perform dissection and vivisection on convicted criminals, benefiting from the favorable intellectual and scientific environment in Alexandria at the time. Prominent physicians from this period who performed “vivisections” ( stricto sensu the exploratory surgery of live animals, and historically used lato sensu as a depreciative way of referring to animal experiments) include Alcmaeon of Croton (6th–5th century BCE), Aristotle, Diocles, Praxagoras (4th century BCE), Erasistratus, and Herophilus (4th–3rd century BCE). Because of the taboos regarding the dissection of humans, physicians in ancient Greece dissected animals for anatomical studies. Humans have been using other vertebrate animal species (referred to henceforth as animals) as models of their anatomy and physiology since the dawn of medicine. The reader interested in a more in-depth analysis on some of the topics reviewed is referred to the reference list for suggestions of further reading.

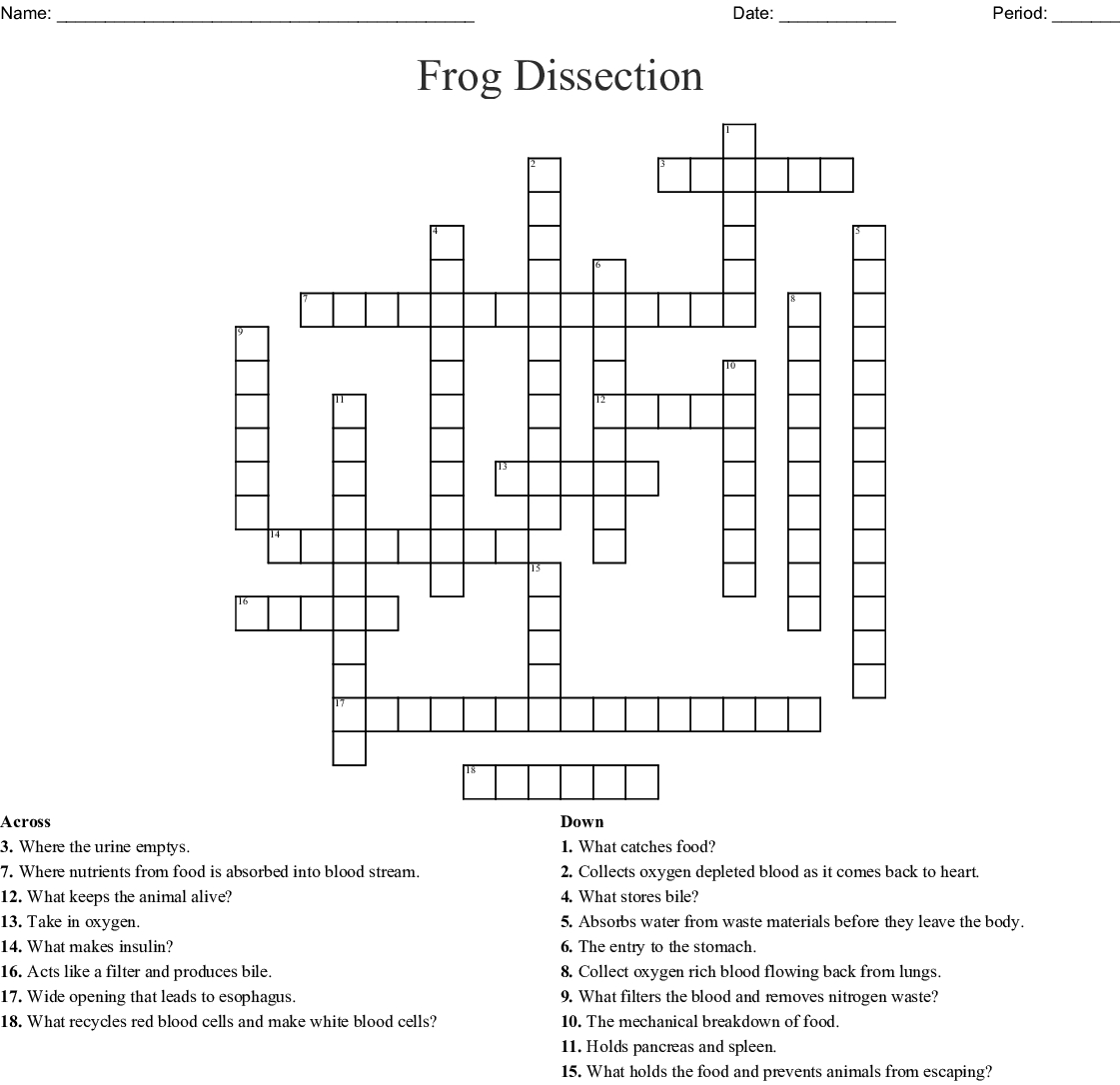

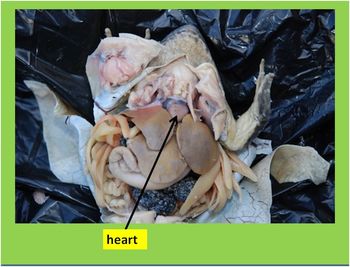

This review aims to provide a starting point for students and scholars-either in the life sciences or the humanities-with an interest in animal research, animal ethics, and the history of science and medicine. This perspective of animal use in the life sciences and its moral and social implications from a historical viewpoint is important to gauge the key issues at stake and to evaluate present principles and practices in animal research. While there are numerous historical overviews of animal research in certain fields or time periods, and some on its ethical controversy, there is presently no comprehensive review article on animal research, the social controversy surrounding it, and the emergence of different moral perspectives on animals within a historical context. For centuries, however, it has also been an issue of heated public and philosophical discussion. These tubes help equalize pressure.Animal experimentation has played a central role in biomedical research throughout history. These are openings to the Eustachian tubes, leading to the tympanic membranes. Two openings can be seen on the lateral sides of the mouth’s roof.The fine maxillary teeth line the upper jaw and the two prominent vomerine teeth are found behind the mid-region of the upper jaw. The esophagus leads to the stomach, and the glottis to the lungs. Identify the glottis and the opening to the esophagus.Cut through the jaw joints on each side of the mouth and open the mouth wide.The cloacal opening, or anus, is the single exit from the urinary, reproductive, and digestive systems. Locate the cloaca at the specimen’s posterior end.

In a living frog, this membrane is clear. This is the frog’s third eyelid, the nictitating membrane. Notice the cloudy eyelid attached at the bottom of each eye.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)